GJON MILI – IL FOTOGRAFO DEL MOVIMENTO

- culturainatto

- 28. Nov. 2021

- 7 Min. Lesezeit

ITA/ENG

di Aurora Licaj

Translation by the author

Cover: Gjon Mili with his cat Blackie, 1946

Gjon Mili è stato uno tra i più importanti nomi d’arte della fotografia del XX secolo: egli fu in grado non solo di perfezionare tecniche rivoluzionarie nel campo grazie agli studi specialistici che caratterizzarono la sua formazione, ma anche di lasciare anche delle vere e proprie opere d’arte fotografiche, immortalando i movimenti di grandi personaggi a lui contemporanei tra artisti, musicisti e sportivi, ma anche momenti di rilevanza storica.

Nato nel 1904 a Coriza, in Albania, si trasferì con la famiglia in Romania all’età di cinque anni, per poi raggiungere a vent’anni gli Stati Uniti e studiare ingegneria elettrotecnica presso il Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), laureandosi nel 1927. Sempre al MIT fu decisivo l’incontro tra Gjon Mili e Harold E. Edgerton, colui che trasformò lo stroboscopio da semplice strumento di laboratorio a dispositivo di uso comune.

Lo stroboscopio è di per sé uno strumento semplice: può consistere in un disco con fori o fessure equidistanti posti nella linea di vista tra l'osservatore e l'oggetto in movimento, che ruota davanti a una lampada e attraverso il quale l'oggetto è illuminato a intermittenza. Se la rotazione del disco avviene con la stessa velocità con cui si muove l’oggetto da studiare, questo si vede dai fori come se fosse fermo (effetto stroboscopico). Nella sua versione elettronica lo stroboscopio è costituito da una lampada molto luminosa che lampeggia fino a un centinaio di volte al secondo. Quando la frequenza dei lampi coincide con quella del movimento dell’oggetto, questo si vede come fermo. È così possibile fotografare su una stessa lastra le sue diverse posizioni durante il moto.

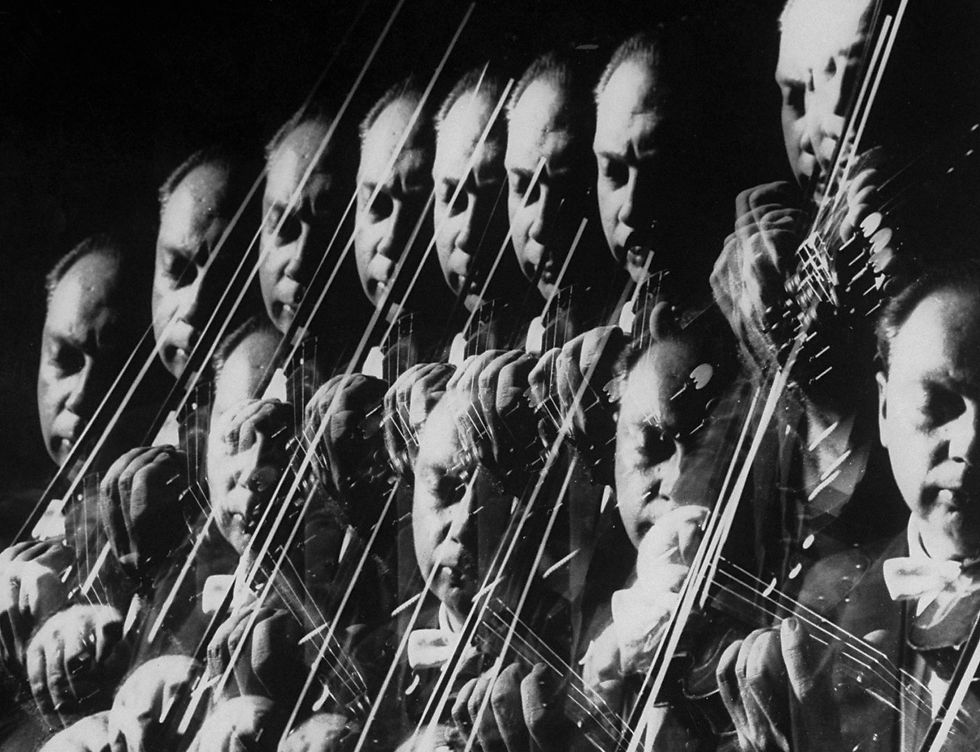

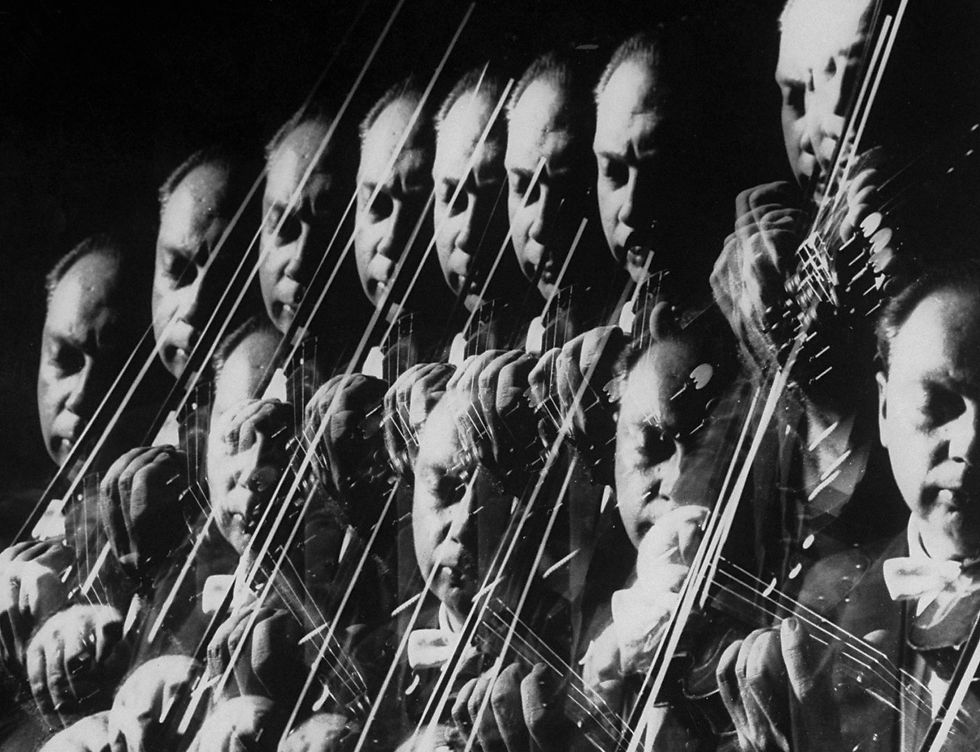

Mili dunque, grazie a questa collaborazione, poté fare sua la tecnica e diventare pioniere nell'uso di flash stroboscopici per catturare una sequenza di azioni in una immagine fotografica, e nonostante fosse autodidatta in questo campo, riuscì ad essere uno dei primi, se non il primo, ad utilizzare il flash elettronico e la luce stroboscopica per creare fotografie non prettamente scientifiche. Grazie alla sua bravura fu assunto da una delle più importanti riviste fotografiche, LIFE, per cui lavorò dal 1939 fino alla sua morte, producendo centinaia di scatti.

Egli cercò di ricreare in studio opere d’arte come il celebre quadro di Marcel Duchamp: Nudo che scende le scale, del 1912, realizzata trenta anni dopo, nel 1942.

In quanto lui stesso musicista sebbene amatoriale (suonava l’oboe), Mili ebbe un sincero apprezzamento per le arti dello spettacolo e nel corso degli anni fece una serie di fotografie di musicisti, ballerini, attori, registi tra cui Alfred Hitchcock, Gene Kelly, Billie Holiday il direttore d’orchestra Efrem Kurtz, il violinista Isaac Stern, il percussionista Gene Krupa, la mezzo-soprano Jennie Tourel, per citarne alcuni.

Nel suo studio fotografò anche le azioni di diversi sportivi famosi nel suo intento di catturare e studiare movimenti impercettibili ad occhio nudo.

Sarà il 1944 che consacrerà il vero genio di Mili, quando diede alla luce al primo capolavoro jazz-filmico della storia “Jammin’ the blues”, prodotto dal grande discografico Norman Granz. Fu un prototipo di reportage, precursore dell’attuale videoclip, che mise in scena i grandi rappresentanti del jazz, nell’attimo preciso del loro sforzo creativo.

I musicisti non sono più rivolti verso un ipotetico pubblico, ma sono raccolti intorno a loro stessi, intorno alla musica che stanno creando. La macchina fotografica si “intrufola” in questa rete fatta di sguardi e intese, cercando di sorprenderla soffermandosi sui volti, sugli strumenti dei musicisti, il tutto in un’atmosfera quasi sognante, data dalla particolare fotografia: un bianco e nero che non ammette sfumature, che scolpisce i corpi, i profili e gli strumenti.

Qui il frammento iniziale dal film col famoso sassofonista Lester Young.

Tra gli artisti figurativi più influenti dell’epoca invece, Mili ebbe modo di incontrare Pablo Picasso nel 1949 a Vallauris, nel Sud della Francia. Le immagini realizzate assieme a Picasso sfruttano in modo sapiente l’uso combinato di luce continua per la traccia luminosa e la luce flash per congelare la figura del maestro ed illuminare l’ambiente circostante. Uno splendido esempio di creatività su tutti i fronti.

In quanto a documentazione storica, Gjon Mili fu inviato sempre per conto di LIFE a fotografare nel 1961 Adolf Eichmann, uno dei maggiori responsabili operativi dello sterminio degli ebrei nella Germania nazista, processato in Israele dopo la sua cattura e condannato a morte per genocidio e crimini contro l'umanità.

L’occhio del fotografo si insinua tra i momenti di quotidianità durante la sua detenzione, rappresentandoli con una quasi surreale intimità, in quella severa e semplice routine che caratterizzava le giornate di prigionia durate le quattordici settimane di processo prima dell’impiccagione.

Nel 1946 si trovava a Parigi per poter richiedere presso l’Ambasciata albanese un visto che gli avrebbe permesso di andare in Albania, ma gli venne rifiutato; nonostante ciò, si ritrovò nel momento giusto per fotografare il dittatore comunista albanese Enver Hoxha, durante un discorso tenuto alla Conferenza della Pace di Parigi in quell’anno, lasciando un’altra testimonianza importante di un evento e personaggio storico.

Si spense nel 1984 all'età di 79 anni a Stamford, nel Connecticut, a causa di una polmonite; nella città natale, è stato realizzato un museo, a lui dedicato, che raccoglie 240 immagini del fotografo.

È divertente ricordarlo con la placca nel suo studio di New York, che proclamava:

“TUTTO IL MONDO È UNA FOTOCAMERA. APPARI PIACEVOLE, PER FAVORE."

GJON MILI – THE MOVEMENT PHOTOGRAPHER

Gjon Mili was one of the most important photography names of the twentieth century: he was not only able to refine revolutionary techniques in the field thanks to the specialized studies that characterized his training, but also to leave real photographic artworks, immortalizing the movements of great personalities of his time among artists, musicians and sportsmen, but also moments of historical significance.

Born in 1904 in Coriza, Albania, he moved with his family to Romania at the age of five, and then to the United States at the age of twenty where he studied electrical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), graduating in 1927. Also at MIT, the meeting between Gjon Mili and Harold E. Edgerton, who transformed the stroboscope from a simple laboratory instrument into a device for common use, was decisive.

The stroboscope itself is a simple instrument: it may be a disc with equidistant holes or slits placed in the line of sight between the observer and the moving object, which rotates in front of a lamp and through which the object is intermittently illuminated. If the rotation of the disc occurs with the same speed with which the object to be studied moves, this can be seen from the holes as if it were stationary (stroboscopic effect). In its electronic version, the stroboscope consists of a very bright lamp that flashes up to a hundred times per second. When the frequency of the flashes coincides with that of the movement of the object, this is seen as stationary. It is thus possible to photograph its different positions during motion on the same plate.

Mili therefore, thanks to this collaboration, was able to master this technique and become a pioneer in the use of stroboscopic flashes to capture a sequence of actions in a photographic image, and despite being self-taught in this field, he managed to be one of the first, if not the first, to use electronic flash and stroboscopic light to create non-scientific photographs. Thanks to his skill he was hired by one of the most important photographic magazines, LIFE, for which he worked from 1939 until his death, producing hundreds of shots.

He tried to recreate works of art in his studio such as the famous painting by Marcel Duchamp: Nude Descending a Staircase, from 1912, created thirty years later, in 1942.

As an amateur musician himself (he played the oboe), Mili had a sincere appreciation for the performing arts and over the years made a series of photographs of musicians, dancers, actors, directors including Alfred Hitchcock, Gene Kelly, Billie Holiday the conductor Efrem Kurtz, the violinist Isaac Stern, the percussionist Gene Krupa, the mezzo-soprano Jennie Tourel, just to name a few.

In his studio he also photographed several famous sportsmen actions in his attempt to capture and study movements imperceptible with the naked eye.

It will be 1944 that will consecrate the true genius of Mili, when he gave birth to the first jazz-filmic masterpiece in history "Jammin' the blues", produced by the great record company Norman Granz. It was a prototype of reportage, a precursor of the current video clip, which staged the great representatives of jazz, in the very moment of their creative effort.

The musicians are no longer aimed at a hypothetical audience, but are gathered around themselves, around the music they are creating. The camera "sneaks" into this network made up of gazes and understandings, trying to surprise it by lingering on the faces, on the instruments of the musicians, all in an almost dreamy atmosphere, given by the peculiar photograph: a black and white that does not admit shades, that sculpts bodies, profiles and instruments.

Here is the initial fragment from the film with the famous saxophonist Lester Young.

Among the most influential visual artists of the time, however, Mili had the opportunity to meet Pablo Picasso in 1949 in Vallauris, in southern France. The images created with Picasso wisely exploit the combined use of continuous light for the luminous trace and the flashlight to freeze the figure of the master and illuminate the surrounding environment. A splendid example of creativity on all fronts.

As historical documentation, Gjon Mili was also sent on behalf of LIFE to photograph Adolf Eichmann in 1961, one of the major operational heads of the extermination of Jews in Nazi Germany, tried in Israel after his capture and sentenced to death for genocide and crimes against the humanity.

The photographer's eye insinuates between the daily life moments during his detention, representing them with an almost surreal intimacy, in that severe and simple routine that characterized the days of imprisonment during the fourteen weeks of trial before the hanging.

(Pictures source: https://www.life.com/history/adolf-eichmann-in-israel-photos-nazi-war-criminal/)

In 1946 he was in Paris to apply for a visa at the Albanian Embassy that would have allowed him to go to Albania, but it was refused; despite this, he found himself at the right time and place to photograph the Albanian Communist dictator Enver Hoxha, during a speech given at the Paris Peace Conference that year, leaving another important testimony of a historical event and character.

He died of pneumonia in 1984 at the age of 79 in Stamford, Connecticut; in his hometown, a museum has been created, dedicated to him, which collects 240 images of the photographer.

It is amusing to remember him with the plaque in his New York City studio that proclaimed:

"ALL THE WORLD’S A CAMERA. LOOK PLEASANT, PLEASE."